I’m not updating this blog as often as I used to. If you want to read more about what’s been going in our (home)schooling adventures, please check out the sites for Red Oak Community School and Over the Fence Urban Farm.

Homeschooling with Shakespeare II

Cora’s interest in Shakespeare, which I wrote about a few months ago, continues…

When we went to vote at the neighborhood middle school in November, we saw signs for an upcoming performance of Hamlet. After inquiring, we were invited to attend to a day-time performance attended by Columbus City School students from a few nearby schools.

Cora was excited to see kids, just a bit older than her, acting out the parts. This version was set in the 21st century, and rather than 14th century Denmark, the location was a video game company. The students used various digital technology to share behind-the-scenes memories – prerecorded videos – and conversations – text message screenshots – between the characters to expand the story they acted out.

We had a good time at the performance and Cora left determined to start acting with her friends. Since then, I have been volunteering at her school once a month, playing improv games and reading through scenes from Romeo and Juliet. We’re having fun, but Cora still wants to spend more dedicated time with kids studying and learning to reenact The Bard’s work. I’m on the lookout for summer camps and other opportunities. If we can’t find any, she has asked me to run one. (Please send leads if you have them! I’m not an actor!!!)

In the meantime, Cora got a new book for Christmas; a collection of Shakespeare’s plays, condensed into short stories by Angela McAllister and illustrated with gorgeous paper collages by Alice Lindstrom. Similar in style to Eric Carle but far more detailed, we have been enjoying examining the images and Cora has excitedly shared them with interested friends who come over.

This week I found her elbow deep in buckets of Playmobil figures (which she hadn’t touched in months), making characters she could use to act out Shakespearean plot lines. This is the kind of independent, playful learning I dream about as a homeschooling mom who aspires to authentic, creative education.

Once she had her cast of characters, I read from her new book as she acted the story with the Playmobil. I wish I had more confidence in making stop motion animation to offer to do that with her. I might have to do some re-search…

Tomorrow we’re visiting The Columbus Civic Theater for The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged). This is one of those times when I’m so happy to be homeschooling. I never studied Shakespeare much myself, so reading the stories with Cora I’ve been introduced to cultural touchstones I see referenced elsewhere and have new understanding of. I’m looking forward to the play as much as she is since this theater is just a mile from our house and I’m ashamed to say I haven’t been there since they opened in ten years ago.

One of Cora’s friends who is also currently hooked on Shakespeare is joining us for the performance. They are going to hang out after and you can bet I’ll be close by, seeing how the play winds its way into theirs.

Homeschooling with Lego

It’s finally feeling really cold and wintery in central Ohio this week and I struggled to get us outside on at all Monday. This is highly unusual for me – a dedicated dog walker who needs to move my body. While our homeschool days are regularly filled with reading, drawing, and playing (educational) games, hanging out inside all day I got the urge to do something different.

Last month, Cora got a few new Lego-related gifts. I found these by searching the web for “gifts to give kids with too many Legos.” This wasn’t because I want her to stop playing with them. On the contrary we LOVE Lego around here – search this blog for Lego and you’ll find lots of posts on the subject. But I wanted to inspire her to do new things with the bricks she already has. Yesterday we dove into one of the books where we met a real building challenge, for mother and child.

Here are a few things I took away from our lesson, which I went into thinking about as supporting girls and innovation. I’ve touched on this topic before, see for example in this brief post about STEAM related picture books.

The first, and ongoing, challenge is finding pieces that meet the supply list for whichever project you choose. At first, Cora selected a project and started building but quickly found she didn’t have certain specialty gears we’d need. Reminded me of times I have started cooking something new without reading the recipe all the way through only to discover I’m missing an ingredient or specially pot or pan I need.

We looked through the book again together and found a project we seemed to have the pieces to complete, though we had to take a lot of liberties finding substitutes for what was recommended. For instance, the walls of our coin bank are made of a range of colors and sizes, not the specific red and gray bricks the author identifies. This seemed like a good lesson about using and being grateful for materials you have on hand, which the author suggests, though the picture perfect images in the book suggest otherwise.

We went through a lot of trial and error, which I was simultaneously happy about and genuinely challenged by. I personally had to fight the desire to give up at least a handful of times. Cora started building a few side projects at some points. I had to remind myself, you are a model right now. If you give up, so will she. I remembered the time Cora asked me to make her shoes that could fit a Barbie doll; the confidence she had that I could do it, and my desire to not let her down. And so we persevered, for hours – losing track of time and reaching a state of flow so intense we nearly missed her piano lesson – until we got the coins to roll down the ramps and into the drawer below.

Amy Brook Snider, PhD: Teacher, Mentor, Friend

Amy Brook Snider was my friend. Our relationship started as one of student and teacher, but over the 20 years since we first met, we became professional collaborators and personal confidants. She was one of the few people who religiously read this blog. I could always count on her to answer emails, be it 11:30pm or 4:15am. Yet, she constantly reminded me that talking on the telephone is the best way to stay truly and intimately connected to loved ones far away.

Amy passed away earlier this month. I will miss her wit and wisdom. She loved to read and collect obituaries from the New York Times. I’m sorry that I can’t write a review of her life on par with what appears on those pages. She was working on a memoir I hope to read someday, and I hope others will be able to read. Her acceptance speech for the National Art Education Women’s Caucus June King McFee Award in 2002 offers some highlights from her life and work. And here are a few things I won’t forget about her.

Amy never met a person she couldn’t make a friend. She was always telling me about someone new she’d met on a line someplace and wound up having coffee with, making plans for a new project or exchanging family photos. It was the same with her students. So many of us approached her about “possible” studies at Pratt, and quickly found ourselves caught in her web.

While she, somewhat reluctantly, got a cell phone a few years ago, she still had a phone with a cord hanging in her kitchen. It was the longest cord I’ve ever seen, ever. When we would talk, I often imagined her pacing around her apartment with that cord trailing behind her…

Amy kept an annotated list of mystery novels she’d read, complete with a short summary and personal review. She took this to the library with her to help her make new selections and ensure she didn’t take home anything she’d read before.

A lifelong New Yorker, Amy had one of the greatest collection of house plants I’ve ever seen. She dedicated half her living room to it, no small thing in small scale, apartment living.

Amy was an true intellectual. Her interests were varied and she read deeply in many areas. I often described her as an “artist’s art educator” because her passion for ideas, images, and objects, surpassed her interest in academic rhetoric, which she had little patience for.

She was a progressive through and through. The last night I spent at her apartment, she dozed off early but called me into her room when Steve Colbert came on the television so we could watch him dress-down The Lump together.

In 2017 she participated in Handwriting the Constitution, a collaborative study of our nation’s founding document. Amy had distinctive handwriting, and always wrote extensive comments on students’ work. She couldn’t help herself. It was part of her feminist approach to teaching, and just being.

I miss you already. I hope you are somewhere wonderful, watching movies and eating chocolate.

Drawing with the D’Aulaires

Cora is in second grade now. It’s hard to believe how fast she’s growing up. She’s reading and writing with greater confidence. And, much to my delight, she’s starting to draw more as well. As regular readers know, children’s independent drawings are one of my passions (see, for example, “Thinking Drawings”).

Sadly, even at her tiny alternative school, kids seem all too eager to judge. She has reported one girl repeatedly mocking her work, calling her drawings “weird.” I tell her to ignore this, that “weird” isn’t a very specific critique, that it’s probably just jealousy, but that only goes so far. Alternately, Cora can name the “best artist” in her class, and often compliments her style.

At the beginning of this school year, Cora was drawing a lot of anime-style eyes – a reflection of the graphic novels that are so popular in her crowd. One classmate taught her to draw eyes like those found in their beloved Amulet series and she learned another strategy by copying the work of a friend. With each of these technical infusions, we saw a proliferation of drawing at home.

The most recent addition to her repertoire came from a study of the D’Aulaires’s Book of Greek Myths. We used the D’Aulaires work last year as part of our homeschool studies of ancient history and were all captivated by the imagery as much as the stories. Recently Cora asked me to help her copy some of their portraits. We started with Cronos and moved on to Persephone.

As she worked we talked about the shapes and angles of the features. She quickly accepted that her drawings wouldn’t look exactly like the originals.

She said she wanted to copy the D’Aulaires entire gods and goddesses family tree, but I anticipated that idea would loose steam. I was happily surprised to see her quickly move on to making her own characters, drawing from a few basic graphic strategies she learned from the D’Aulaires’.

All this reminded me of Paul Duncum’s (1988) survey of ongoing debates about copying in art education. Duncum outlines at least five positions on the copying debate in art education, citing literature and drawing out intermediary positions between the traditional polarities of to copy or not to copy. He writes, “According to one position, copying is utterly undesirable under any circumstances. Indeed all forms of graphic influence are bad” (p. 204). Limiting all forms of graphic influence would be impossible, of course, unless a child is raised in a cave with no outside stimulus. Certainly, children growing up with picturebooks and cartoons and museum visits (or just in the 21st century culture of constant media bombardment) are exposed to various styles of representation, some of which will make it into their own doodles and more formal works of art.

Duncum cites others who advocate copying as a “necessary part of learning to draw because all drawing is based on previously acquired representational schemata” (p. 205). Brent and Marjorie Wilson (1982) and Olivia Gude (2004) have argued that some copying, referred to respectively as “borrowing” and “appropriating” which both sound a lot better and more thoughtful than copying, can build confidence and provide children with fodder for their own creative inventions. My husband concurred in a recent commentary on Cora’s work: “I freaking love the confidence in her lines. Go for it Cora Lena!”

Homeschooling with Shakespeare

Well, it’s been another long stretch since I posted anything in this space. It’s not for lack of thoughts of desire. I just need to make time for it again. I did write a personal essay for a journal that was based, in part, on my work in this space. Maybe if the feedback on that is positive it will motivate me.

In the meantime…

Following up on my last post, I’m back to part-time homeschooling with my daughter, who was the initial inspiration for this blog six years ago. Cora just turned 8 and is a second grader at Red Oak Community School the days we aren’t together. This fall we’ve been spending time with William Shakespeare. This was largely inspired by her first trip experience with Shakespeare in the Park late this summer. The magic of sitting outside as the sun went down and actors ran around (on and off) the stage at an Actor’s Theater of Columbus presentation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream captivated her immediately.

Cora talked about the performance for days following. This coincided with my reviewing notes for second grade homeschooling in A Well-Trained Mind (AWTM), one of the tools I use to help determine what to focus on during our homeschool days. This year’s social studies (see Story of the World: Volume II) and literature curricula include Shakespeare, though not until the end of the year. Since I’m the teacher, striving to embrace a a student-driven learning pedagogy, I decided to follow Cora’s interest. I used the resource guide in AWTM to identify materials for kids about Shakespeare including the amazing series Shakespeare Can Be Fun by Lois Burdett. While I take issue with the series title – why imply Shakespeare isn’t fun?! – the content is amazing.

Burdett wrote the series while teaching elementary school in Canada. There is surprising little about her or this work online, though it is clear she gave it her heart and soul. The books are layered with content starting with Burdett’s abbreviated versions of The Bard’s plays written in language kids can understand more easily than the originals, but retains his poetic voice. I believe she used these with her students to stage performances which are documented in photographs at the front and back of the books. Cora and I have been working together to interpret the meaning behind some of the lines like this one from Hamlet, “You don’t know how I feel. My pain these mourning clothes conceal.”

In addition to Burdett’s versions of the stories, each page includes drawings by her students (ages 7-10) and their own writings in response to the story. These include cleverly composed diary entires and letters written in the voices of the characters. There is a list of recommendations for these and other extension activities in the back of each book. The homeschooler in me is a little jealous of how well the kids seem to write for their age. But, I also noticed the handwriting looks pretty similar across student authors and I’m wondering if that was something the publisher had a (heavy) hand in…? Or is this just the result of lots of practice?

From Burdett’s Hamlet (2000).

The drawings demonstrate close study and understanding of period dress and settings. The art educator in me would like to know more about her process for guiding drawing assignments. I’m sure the kids were using reference images in some way, which I am not at all against. Though I curious how she introduced this strategy, how she fit it into her curriculum overall, and how she guided the kids through multiple drafts of their work. I think I’m going to send her an email and see if she can share more information on this and the project in general.

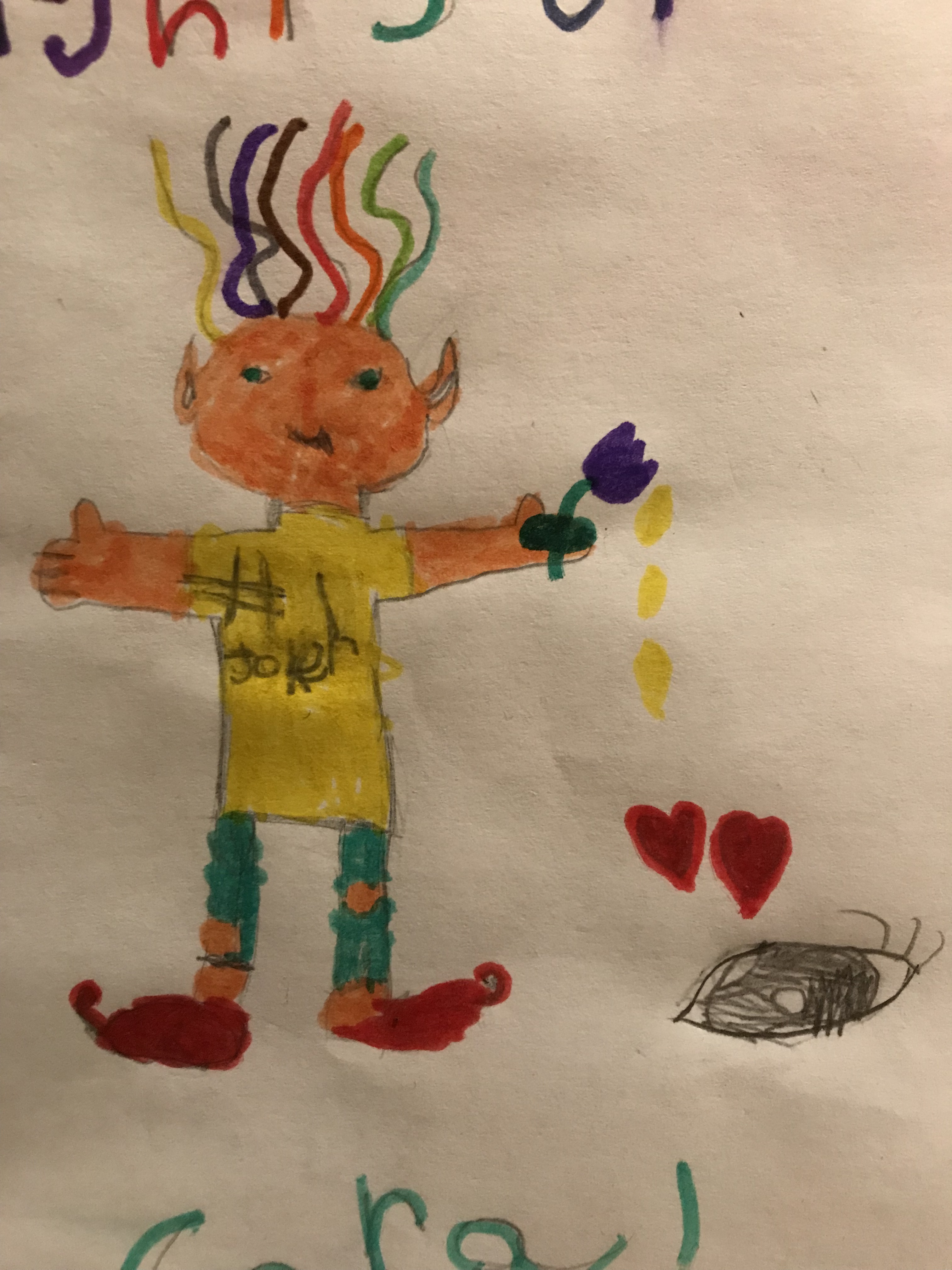

Cora has been making some of her own drawings while we read (see below). They aren’t nearly as detailed as Burdett’s students but represent her way of making sense of and representing the texts visually. We might try looking up some fashion history as inspiration. If we do, I’ll try to report how it goes.

Puck, #1 Jokster with the magic flower within which eye drops of love are found.

Of course we started our deep dive into the works of William Shakespeare with A Midsummer Night’s Dream. After that we moved onto Shakespeare Retold (Nesbit and Caparo, 2016) which offers short, narrative versions of 7 plays. We have a short stack of Burdett books we look forward to working through and Cora is starting to talk about whom among her friends might be good acting partners. It’s been a good start to the year.

NAEA 2018 Preview: A Return to Picturebooks through The Land of the North

Next month, my friend Amy Brook Snider and I will be sharing the latest installment in a series of presentations we’ve given at the National Art Education Association Convention. The subject of our presentations has spanned a range of enduring topics of interest throughout our relationship and conversations on the telephone.

“Indivisible: A Consideration of the Picturebook, Past and Present” will include a slide show on some great moments in picturebook history. We’ll share criteria for identifying great picturebooks and some of our personal favorites. We hope our session will remind art educators of how the picturebook functions as works of art, one readily available to children and worthy of attention in the art room.

Preparing for this session has led me, quite happily, back to the picturebooks section of the library. As I shared in the fall my daughter (and co-captain in life the past seven years) Cora’s attention span for listening to stories is astounding and she will sit for hours being read to from chapter books. As her capacity to listen longer and her hunger for more complex and developed stories developed, we largely moved away from picturebooks. But as Amy and I reaffirmed through our conversations and investigations, great picturebooks are not just for children, and everyone in our house is happy to have them around again.

This fall, Amy reminded me of the D’Aulaires, a couple who emigrated from Europe to the U.S. in the early 20th century and went on to write and illustrate more than two dozen books. Their books were also included in a classical homeschooling curriculum we’re playing with this year. Cora and I started with their Book of Greek Myths (1962). (Note: We also LOVED Aliki’s Gods and Goddesses of Olympus (1994).)

The D’Aulaire’s storytelling is vivid and their detailed illustrations are captivating. They captured the most essential aspects of their plotlines through detailed drawings that could stand on their own as works of art. First depicted through 4-color lithography and later layered drawings on acetate echoing that process, these images are sure to stick in readers’ minds.

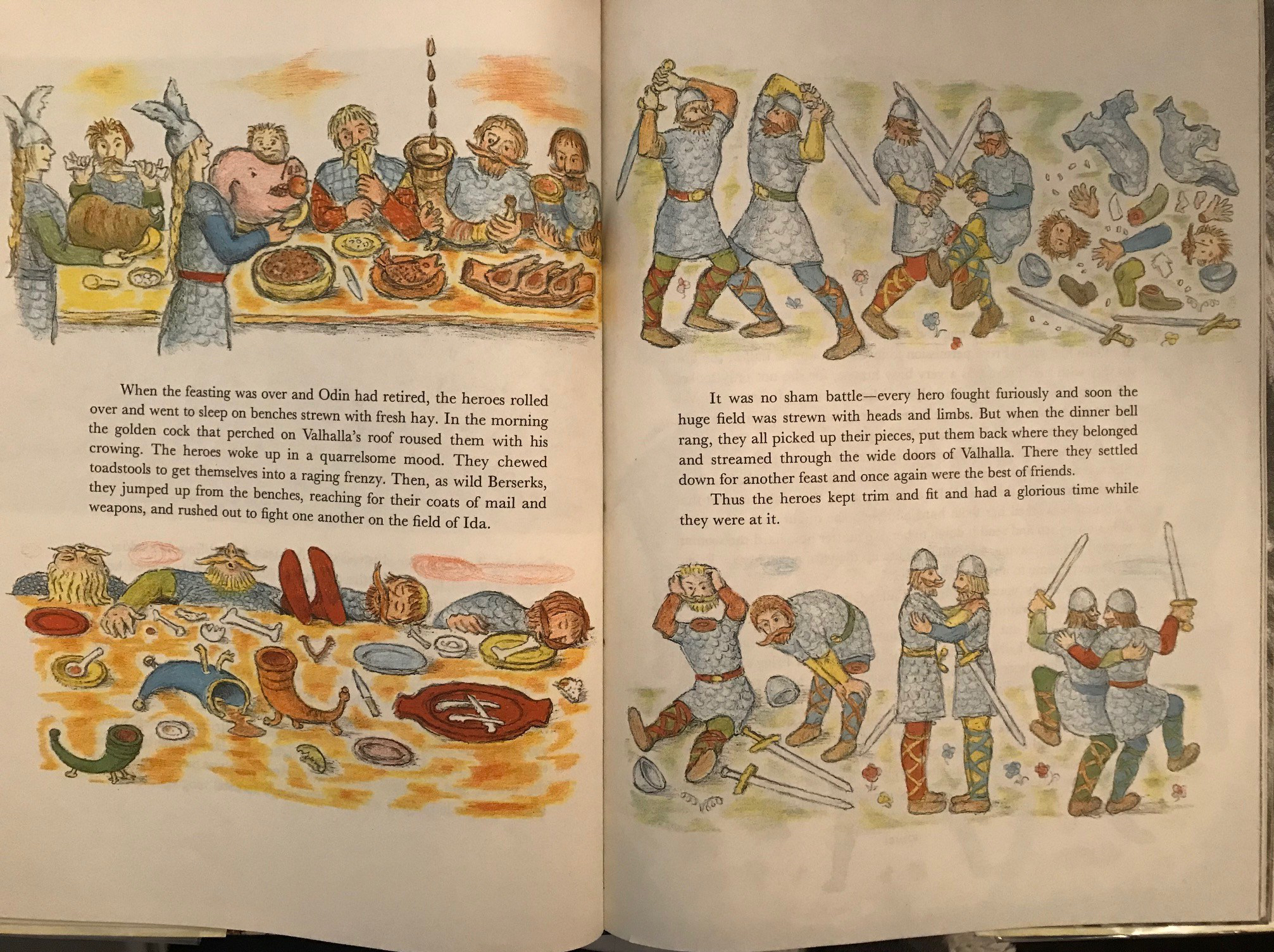

We currently have at least half a dozen of their books out from the library including Norse Myths (2005) (initially published as Norse Gods and Giants (1967)). We started reading it on a snow day last week (which felt appropriately hygge) and have been devouring it. We are having fun using the glossary to pronounce the Norwegian names. And we’re findings lots of characteristics in the Aesir that mimic the Greeks and other literary characters we know.

While my days with Cora have been filled with Odin and the Aesir, my nights have been spent watching Game of Thrones. The parallels are astounding.

I was not the kind of kid who read fantasy growing up. I never collected crystals or played Dungeons and Dragons. As an adult, when friends first started talking about Game of Thrones I tuned them out. But as a parent, I’ve been given a second change to engage explorations of good and evil through more recent mythologies like Percy Jackson, Harry Potter, and The Lord of the Rings.

Game of Thrones is intense. I didn’t have any idea what we were marching into when I suggested to Dan that we turn it on a few weeks ago. I was immediately drawn to the costumes, settings, and characters, at the same time that I was repelled by most of their behaviors. But reading Norse Myths, their intense embrace of all parts of life, death, war, sex, food, etc. makes more sense. The northerners in the story are clearly designed after the Norse, such as that depicted in this story of Odin’s heroes. After fighting to their deaths in Odin’s name, they were granted flown to the world of the gods by beautiful maidens to an afterlife full of all out feasting and fighting (and quiet time with women when their mood allowed).

The D’Aulaires’ share stories that have formed the touchstone of many Western literary and artistic projects. I’m grateful to be reading them so closely now, wishing I hadn’t waited so long.

[Note: Apologies to loyal readers who have missed updates from me through this space these past months. I have thought of this project often, but been pulled in other directions. In case I fall off the map again, come look for me at overthefenceurban.com and http://www.redoakcommunityschool.org/rocs-blog/]

A Report from Tinkergarten

This is my 8th year teaching for the University of Florida Online Master of Arts in Art Education program. Through the years, I have had the opportunity to work with art educators across the country doing amazing things. I showcased a few in this space with posts dedicated to their capstone projects (See “Time to Brag” and “Creamery Hill Racers,” for example). I intended to make that a regular column, but time got the better of me. Maybe this winter…

As any educator knows, one of the greatest gifts our students can give us is coming back with reports of how a course one taught, a reading one assigned, or a comment one made changed the way they think or behave. And so it was with great pleasure that I found this post on our program’s Facebook page one day this summer.

Another item on my perennial list of the “things I’ve wanted to do in this space” was to invite students and alumni to share their ideas and experiences. With that in mind I asked Natalie to write something about Tinkergarten. According to their website, “Tinkergarten provides high-quality early childhood learning in the healthiest classroom of all—the outdoors. Families connect with trained leaders in their local community for play-based kids classes that help develop core life skills, all while having fun!” The following are Natalie’s thoughts on the program, drawing on her knowledge and experience as an art educator.

“Natural Education” by Natalie Davis

Sydney darted across the park with her backpack yelling “Miss Betsy! Miss Betsy!” She was so excited to show her teacher her red galoshes. It was mud day and my three-year-old little girl was extremely excited to get dirty and start her play-based outdoor classroom, Tinkergarten.

What is Tinkergarten?

It is not your typical classroom. In fact, it is the complete opposite of a brick and mortar school. There are no walls and there are no desks. Children are not required to walk in single file lines. Use of digital technology is prohibited. Rather, a Tinkergarten class takes place in a park or other green space in the local community. The concept is simple: playing in nature and learning go hand-in-hand. Sticks become drawing tools, mud becomes paint and flowers become collage items. The outdoor play-based activities are not only fun but also cognitively stimulating because they encourage children to explore. The learning environment is as authentic as the surroundings.

Why Tinkergarten?

As an art educator and mamma, I was drawn to Tinkergarten’s philosophy of play-based learning. I welcomed the opportunity for Sydney to learn through innovative approaches to curriculum I was familiar with from art education like Waldorf, Reggio Emilia, Forest Kindergarten, and Montessori (Tinkergarten, 2017). Like Dewey (1925), Froebel (1887), Lowenfeld (1949) I know it’s important for young children to be in and explore the natural world, and use their biological desire of playing to inspire and enrich their thinking. As an art educator, I followed this philosophy in my own teaching career and witnessed success first hand. I wanted that kind of learning for my daughter.

How does play turn into learning?

The word play sometimes can be misconstrued as useless recreation. This is definitely not the case during a Tinkergarten class. The class has a trained facilitator referred to as the Leader. The leader sets up playful invitations and activities designed to enable the children to take an active role in learning. The children’s natural curiosity guides the learning experience. I strongly agree that these types of activities are “the best way to help nurture kids’ development and ready them for academic success later in life” (Tinkergarten, 2017, para 4).

The Leader’s role is not to ensure completion of the activity as might be assumed. Instead they are there to help guide children into deeper understanding by capitalizing on situations that excite interest in each individual child. They use these opportunities for educational enrichment.

For example, my daughter came across a worm and a bug while digging in the mud. Her discovery led to conversation. The leader prompted my daughter and the class to talk about the worm and bug. They discussed their purpose, textures, and colors. Digging in the mud was turned into making a “worm hotel habitat” out of a mason jar. In another area of the park, a child found a rock while digging in the mud. The little boy held up the rock and announced his discovery to the class. As more children gathered around to see his treasure, he dropped the rock into a large bucket of water. The Leader seized the opportunity for enrichment and suggested to the group to make a special “soup”. The Leader’s suggestion led to an outpouring of imaginative responses from the children. They began discussing the “special soup ingredients” and ran off helping one another to gather them. They collected foliage, rocks, and flowers to name a few. In this moment, the children were working on social skills, motor skills, collaboration, creativity, and problem solving.

Final Thoughts

A few years ago, in a course in graduate school, I read an article that intrigued me on the subject of technology in the classroom. The article described a trend among Silicon Valley CEO’s who enroll their own children in nature-inspired Waldorf Schools (Richtel, 2011). I was fascinated to learn that technology leaders saw value in using nature and limiting technology in their children’s education. I added it to the list of reasons I might pursue such experiences for my daughter.

References

Tinkergarten, 2017, Retrieved from https://www.tinkergarten.com/leaders/betsy.modrzejewski

Dewey, J. (1925). Experience and Nature. Chicago & London: Open Court.

Froebel, F. (1887). The Education of Man. (Translated by Hailmann, W.N.) New York, London, D. Appleton Century.

Lowenfeld, V., & Brittain, W. L. (1970). Creative and mental growth (5th ed.). [New York]: Macmillan.

Richtel, M. (2011, Oct. 22). A Silicon Valley School That Doesn’t Compute. [Essay on New York Times]. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/23/technology/at-waldorf-school-in-silicon-valley-technology-can-wait.html

Review: Scholastic ART

Time has not been my friend lately and I’ve been neglecting this blog. I was brought back today by an invitation I received at the end of June from Katie Brickner, Editor of Scholastic ART magazine and online content.

Katie asked for an “honest review,” and I accepted. She sent me a complimentary set of the magazine from 2016-2017 and access to the online resources available to paid subscribers and their students. She’s also promised a 2017-2018 class set which I plan to give away to one of my former students.

The project and accompanying online video, “Paint an Identity Portrait,” were disappointing. While it started with a reference to Crosby, the project guide focused on formal aspects of making a portrait – choose a subject, develop a color palette, use a range of brushstrokes, work carefully, etc. It didn’t emphasize anything that reflected Crosby’s specific approach to portraiture which incoroprates “layers images, textures, and symbols from many sources [to] visually present her varied cultural experiences” and would require an artist to know or interview her subject and gather materials to weave into the work that would reflect the identity of the subject.

During a quick survey of students and alumni from the University of Florida Art Education program I heard from both teachers who subscribed to the magazine and those who just made use of the samples they received from Scholastic. They reported that they got some good ideas from the magazine. However, most felt it was just a start which they usually had to follow-up with additional research of their own. For example, “They chunk information in a way that is clear yet informative, however, I have found for more meaningful explorations, this is only a starting off point.”

My students reported using Scholastic ART projects as makeup work and as substitute plans. They suggested that it “made life easy” to have something written out in advance that they could leave and someone else could follow. For example, “If it happens to be one of the “artsy” subs of the county they will add some of their own directives. But if it is just a “regular” sub the lessons tend to be more cookie cutterish.” This speaks to my own criticisms of the plans, they are fairly rudimentary and don’t speak to the intellectual or social dynamics of artmaking.

While I wasn’t impressed with the project recommendations, I appreciated the “Debate” column which addresses the oft ignored aesthetic component of DBAE-inspired art education. Each magazine presents an issue for students to consider and debate with their classmates. In the Painting Right Now issue, for example, students read about a pair of European artists who have been painting pigeons bright colors to see if they attract more attention than usual (see below, left). The essential question posed was, “Is it right for artists to capture and paint live animals in the name of art?” Online, students can leave comments, read from others, participate in a similar conversation in a larger public forum with student readers from other schools (see below, right).

In the end, Scholastic ART is a resource, like any other. It can aid teachers in their work, but it can’t replace us. It is a tool, but must be used in conjunction with other materials to successfully build something. One new direction I can imagine for Scholastic ART would be a hosting a forum (on their website or Facebook) for teachers who subscribe and use the magazine to share ideas for how they use and extend the materials presented there. This would help push the teachers, as well as the editors in their future work.

I’m curious to learn more about how teachers are using the magazine. Do you subscribe? If so, how do you use it in your classroom? Do you ask parents to cover the cost using Scholastic’s “Parent Funding Request Letter?” What recommendations would you make to the editors to help them improve and extend their offerings?

Process Art’s Pesky Problem

Mousetrap paper holder. Or, as I see it, surreal assemblage.

Over the years, I’ve written a lot in this space about the value of process art (see for example Doing Food Coloring and Permission to Play: Toddler Paint Bomber). My interest started when I was an undergraduate and developed an intense appreciation for the Abstract Expressionists. Learning about their work and the questions they engaged with in their studios – exploring the inherent nature of the materials they worked with – became an obsession. I developed my own color field experiments and filled huge sheets of paper with marks based on systems I devised. It was visually engaging in an allover sort of way, but I knew it wasn’t nearly as interesting for others to look at as it was for me, with my embodied knowledge of the actions I took to make it.

In the years since, I have continued to develop my relationship with questions like: What is art for? and Why art? I have carried these into explorations of art criticism, visual culture, environmental and installation art, relational aesthetics, and creative placemaking.

This interest also manifests in my advocacy for process art in the playful learning of young children. Really, I believe children of all ages looking for new ways to connect with creative activity ought to focus on process (see for example, Permission to Play: Birthday Parties and Grandma Joyce’s Beautiful Stuff!).

And so it was with a heavy heart that I set about cleaning Cora’s desk yesterday. Stacked on top were the traces of two weeks of summer camps and a few final school projects.

(Note: I took this photo AFTER I had cleaned the desk and decided to blog about it. I stacked the artwork back up in an approximation of how it had been. But absent are the dolls, rocks and sticks, books, and other random crap that had been there too.)

As Dan has observed, all horizontal surfaces in our house quickly become repositories for junk and this desk is no different. In the three years since it has been in this location, I can count on one hand the times that it has been clear and Cora has sat at it to do anything. I have a plan for it in my head related to a pen pal project we’ve been working on (fodder for a future post), so I told her it was time to clean up.

Of course Cora wanted to save EVERYTHING.

The art camp she attended last week at a neighborhood studio (Paper Moon Art Studio – Columbus, OH) was a great process art experience for Cora. She got to work with a range of media from paper mache to assemblage (complete with hot glue, see the top image on this post), and sand painting to watercolor. She was only there three mornings, but she made a ton of stuff. We had trouble carrying it all home! I was so happy to see this evidence of experimentation but what to do with all that stuff? I live in constant battle against clutter – mostly this involves shoving piles into drawers and cabinets when guests are due – but point being, I don’t like to have a lot of stuff sitting around on horizontal surfaces.

I also struggle, personally, with the hidden curriculum we are teaching kids when we give them access to unlimited supplies and let them make things that will ultimately, at least in my house, wind up in the trash. I has this same feeling while attending TASK parties run by Oliver Herring (see A Task, But Not a Chore). I love the energy that Herring creates and the collaborative experimentation I see at these events, But at the end of the day, there are piles and piles of materials left in a jumble on the floor. A few ideas for combating this issue come immediately to my mind.

Art educators will see the immediate irony in this. Many of us have felt the pain of watching students put their artwork in the trash bin on their way out the door at the end of a term. All that time and effort? Don’t they care at all about what they made here? And, by extension, don’t they value me and our time together? Some educators even use this as a litmus test for a successful lesson — Do the kids express desire to hold onto what they made? to share pictures of it in Instagram? to hang it up at home, or give it to someone as a gift?

So now I’m left holding this evidence of creative activity, all of which Cora insists on calling Art (capital A intended) in an effort to use what I value against me. And I’m wondering,

How can we simultaneously teach people that some things they make are precious and others are not? That some creative experiences are about the process of making, and some about the product that results?